Amazing facts about India

From 1 CE all the way through the next two millennia up to 1700 CE, all the large scale industries like mining, metallurgy, textiles, arts, and crafts flourished in India. They boosted trade to such an extent that India held about 1/4th of the world’s GDP (Gross Domestic Product). Yes, the economic history of India is truly astounding.

Angus Maddison, a British economist, ingeniously traced the economic history of India across 2,000 years starting from 1 CE in his study of the global economy. He focussed especially on the rich and the lagging regions of the world, the reasons for their richness and poverty respectively, and influence of each on the other’s economy.

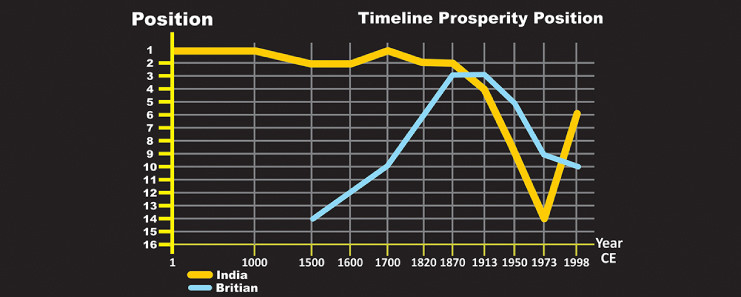

The data put forth by him , published by OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development), also showed India to have been the economic giant of the world for 2,000 years. India ranked number 1 in the list of nations with the highest share of the world’s GDP at close to 25 percent from 1 CE all the way through the next two millennia upto 1700 CE, after which it drops sharply during the British rule.

Consistent performance for over more than 2 millennia

As per Angus Maddison’s report, if in 1 CE itself, India’s share of world GDP was 30 percent, it implies that that could have happened only in two ways:

* it would have either risen to that number steadily over the preceding few millennia or

* it may have declined from an even higher value over the preceding few millennia.

In either case, it means even prior to 1 CE, India was enjoying a high degree of prosperity.

These reports were further corroborated by the fact that:

* 2,000 years ago, with its surplus exports to Egypt and earnings in gold as returns, India was making Roman Egypt bankrupt of its gold reserves. (Records of the Economic History of Greco-Roman World.)

* the Indian Merchant Navy had possessed a fleet strength of 40,000 ships during Akbar’s reign and 34,000 ships before the British took over India. (The historical records of the Indian Merchant Navy)

* between 1493 and 1930, India had absorbed 14 percent of the world gold production, meaning that it had earned that much export surplus for five centuries continuously. (The 1934-35 annual report of the Bank of International Settlements [BIS].)

From the village to the city

The generations of today have grown with the belief that wealth lies only in the cities, because of their industries and trade. However, a study of the economic history of India shows a stark contrast to the reality of today: medieval and ancient India worked on a different modus operandi.

The economic history of India reveals a secret:

The wealth of the nagara mainly came from trade. The wealth of this land came, not from colonial exploitation but through sustainable internal resource mobilization – proven, local, self governance.

It was the villages and small towns that were prosperous. They were the centers from where prosperity flowed. Prior to the British period, a lot of wealth was generated in the hinterland, the villages, grama, mainly due to the prolific practice of agriculture, multiple bountiful harvests and many small-scale industries abounding in every village of the land. This, in turn, supported the nagara, towns and cities of ancient India.

The wealth of the nagara mainly came from trade. The wealth of this land came, not from colonial exploitation but through sustainable internal resource mobilization – proven, local, self governance. A very different picture from today’s modern India.

Rise & fall

The supremacy of India in the world of trade has been brought out by the modern economist Paul Kennedy in his book, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers. He observes, “India’s share in world trade, which was a very healthy 25 percent of the total world trade, drastically dropped to a decimal percentage in a span of 200 years, which was the period of the British rule of India.”

Prof. David Clingingsmith and Prof. Jeffrey G. Williamson, of the Harvard University in their work, India’s De-industrialization in the 18th and 19th century, mention the impact of 200 years of British colonial rule in India. They write, “India was a major player in the world export market for textiles in the early 18th century, but by the middle of the 19th century, it had lost all its export market and much of its domestic market. While India produced about 25 percent of the world’s industrial output in 1750, this figure had fallen to only 2 percent in 1900.”

To conclude, 300 years don’t seem so long ago. The past could become the promise of our future as well.